Developing Partnerships through the Nonprofit Certificate Program

Posted in News Story Spotlight

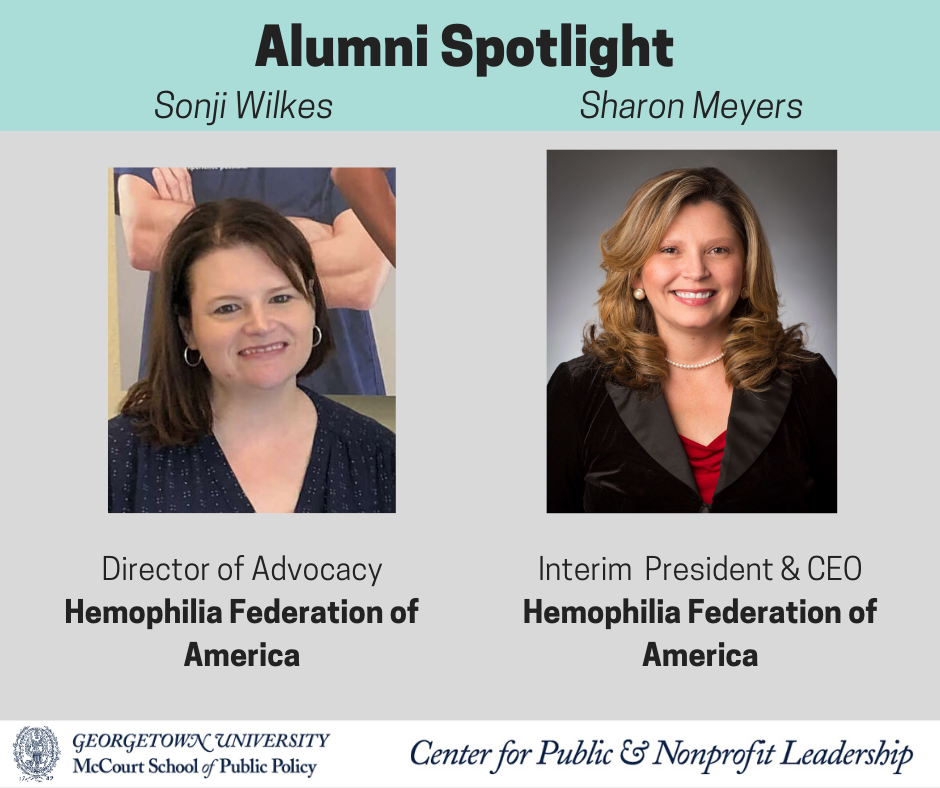

Hemophilia Federation of America, Inc. (HFA) is a patient education, services and advocacy organization serving the rare bleeding disorders community. Based in Washington, D.C., HFA consists of a national organization office and more than 50 local community-based affiliated organizations made up of numerous men, women, and children impacted by a bleeding disorder. The Center for Public and Nonprofit Leadership spoke with alumna Sharon Meyers, HFA’s Interim CEO, and incoming student Sonji Wilkes, HFA’s Advocacy Director, about their experiences working in the nonprofit sector and the Smithsonian partnership that resulted from their involvement with CPNL’s Certificate Program.

Why were you interested in partnering with the Smithsonian Institution?

Meyers: The Hemophilia Federation of America (HFA) had been trying for many years to have the history of the bleeding disorder community recognized. It’s important that people know this history and it’s not something you can read about in most textbooks.

Wilkes: Many people aren’t familiar with the history of the bleeding disorder community in our country. During the 1980s, 90% of people with severe hemophilia were infected with HIV or Hepatitis C. We lost an entire generation of our community. Subsequently, we did some very aggressive legislative advocacy to receive compensation from the federal government. There were several breakdowns that introduced HIV into the blood supply in the first place, from regulatory to pharmaceutical to medical. We have been trying to get that story out there. We want everyone to realize that because of the hemophilia community and our activism, our country has a safer blood supply today. We also want to honor the thousands of people we lost.

How did the Certificate Program make it possible for you to connect with the Smithsonian Institution?

Meyers: I came to HFA four years ago. Around that time, our CEO expressed the desire to have our history showcased and conserved by the Smithsonian, to ensure that it is saved for the world and our community. However, it’s not an easy task. You can’t just show up at the Smithsonian and say, “Hey, our community’s history is super important.” We discussed this several times at HFA before I joined the 2017 Nonprofit Management Executive Certificate summer cohort with James Zimmerman, who works at the Smithsonian. When I saw his name, I told my boss that I was going to sit next to him and explain our cause. We were at dinner the second night of the program when I sat next to James and talked to him about our history at HFA.

In class the next morning, he handed me a post-it with a woman’s contact information and said we should contact her. We weren’t really sure who the woman was at this point, but it was a name and a number! We set up an appointment between her and my CEO that same day. We came to find out that the woman was the curator of medical history for the American History Museum. James didn’t just connect us to an associate manager or coordinator; he connected us to the head of the department relevant to HFA’s work. He came through big time! The whole time I was in class, I knew my boss was meeting with the curator and the idea that we were so close to our goal was exciting.

What historical information were you able to share with the Smithsonian?

Wilkes: After the initial meeting, we maintained a relationship with the curator for about two years, reviewing the artifacts we already had, what we envisioned for this possible exhibit, and what parts of our history the Smithsonian wanted to showcase. By April 2019, we had collected around 25 oral histories, which were part of our first round of donations to the Smithsonian archives. Everything from journals to old medical books to litigation documents was included in our submission. In September 2019, we submitted round two of our archive donations. We don’t necessarily expect a physical or permanent exhibit, but everything we provide will be digitized and available to an international community of researchers for the next 300 years. It is the legacy of our community secured. When we announced it at our yearly conference, the room exploded with emotion and excitement. We have literally been fighting for recognition for decades.

Meyers: The Nonprofit Management Executive Certificate Program was us being at the right place at the right time, and not being afraid to advocate for ourselves and our community. James coming through the way he did was just meant to be. He is simply a wonderful person with a heart for service.

Were there any major challenges? What should someone who might work in partnership with an institution like the Smithsonian know?

Wilkes: The hardest thing for us was keeping so much of our progress private. For almost two years, we were working on it behind the scenes, but we couldn’t tell anyone. When we were reaching out to people during HFA’s 25th anniversary as an organization, when we were requesting oral histories and archival histories, literally searching through boxes of history at people’s dinner tables, we couldn’t bring up the Smithsonian. The secrecy was really hard. It was also difficult to coordinate schedules and communicate on a regular basis with such a busy organization.

Meyers: The Smithsonian is obviously a very busy place and we really needed to be patient, even as we were ready to move forward.

What drew you to work for the Hemophilia Federation of America?

Wilkes: In 2003, my son Thomas was born and the day after that, when he was circumcised, he continued to bleed. He was then diagnosed with severe hemophilia. In about 70% of cases, there is a family history that informs you of the chance of having a child with hemophilia-related disorders. In our case, there was a spontaneous mutation of a gene. We later found out that I carried the gene for hemophilia. Having Thomas is really what drew me to HFA. I already had a background in programming and advocacy work. For me, being on staff at HFA is the perfect marriage between professional background and personal passion.

Meyers: I previously worked at a hospital in Denver. Sonji told me about a position that was opening at HFA. I didn’t have much knowledge about bleeding disorders beyond my work as an EMT years ago, but Sonji was persistent, so I spoke to the woman retiring from the position. I quickly fell in love with the work, the community, and what our advocacy can do to ensure the quality of life for those living with these conditions.

Sharon, what was something you got from the CPNL certificate program aside from this partnership?

Meyers: Aside from meeting James, networking and collaboration with other students were the most important parts for me. The education was top-notch. It was a high-level education in a helpful format that worked with my schedule. Through the program, you see the similarities with other organizations and share in solutions. I found camaraderie with my fellow students and a love for being in DC, where the action was. I enjoyed it so much so that I encouraged Sonji to attend.

Sonji, what do you hope to gain from the program this spring?

Wilkes: I spent 12 years raising my children. When I returned to my career, I felt behind. I had experience but had to start at entry-level work again, fighting my way up the ladder. I know I need some of that professional development and “secret sauce” to back that. The program is exactly what I need, knowing how valuable the experience and connections were for Sharon.