Pandemics and Protests as a Portal for Change: A Guide to Never Returning to Normal

Posted in News Story

By Jennifer Sullivan

July 2020

Jennifer Sullivan is the Director of Housing and Health Integration at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. She participated the Center’s Nonprofit Management Executive Certificate Program and this article was written for her capstone management project assignment.

The full article with figures and endnotes can be downloaded here.

Introduction

However nonprofit organizations began the year 2020, whatever goals had been devised at annual planning retreats or over lengthy strategic plan meetings, no organization had planned for the abrupt end to “business as usual” and the profound disruption that would follow as the COVID-19 pandemic and resulting economic crisis took hold. Fortunately, many organizations (particularly those without a direct service component) were able to continue advancing their mission despite office closures, as long as they were willing to make rapid and dramatic adaptations to how work gets done. Nearly three months into this new adapted state, the murders of Black Americans Ahmaud Arbery, George Floyd, and Breonna Taylor ignited nationwide protests that forced even the most progressive organizations to reckon with whether their mission, program, funding, and policies were truly anti-racist, or potentially part of the problem.

Now, as leaders of these organizations map out the course ahead—peppered with additional uncertainties, ranging from whether there will be second and third waves of pandemic-driven devastation, to how funders will react to a tumultuous economy, to the outcome of the 2020 elections—they must also grapple with when, and how, and whether to reopen their brick and mortar offices. What adjustments worked so well that teams are reluctant to revert to the “old” normal? What bold changes will leaders and funders be willing to embrace in the face of unprecedented attention to structural and systemic racism?

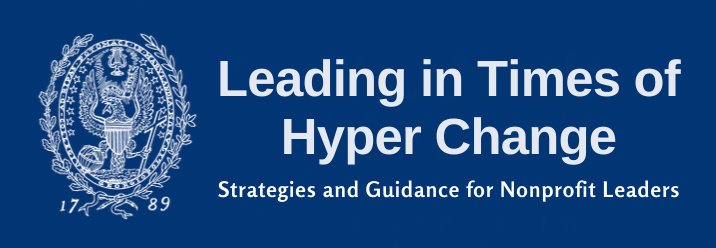

At this inflection point, nonprofit leaders have a tremendous opportunity to radically transform their organizations in ways that better meet staff needs, demonstrate the organization’s commitment to its values, and cultivate an antiracist work environment, all of which can enable organizations to more effectively advance their mission. See Figure 1.

Returning to the old ways of doing work would be more than a missed opportunity; it could actively harm staff morale and retention as well as jeopardize the future sustainability of the organization.

This guide is designed to help nonprofit organizations seize the unusual opportunity to leverage learnings from this time of hyper change and rebuild a higher-functioning, more nimble organization. It is divided into four sections:

- Employee Experiences Exclusively Teleworking: What has gone unexpectedly well? Predictably poorly? How does this relate to the future of how work gets done?

- Policy Toolbox: A menu of changes organizations could consider introducing or institutionalizing

- Action Planning: What leaders need to do to prepare themselves, their executive team, staff, and funders to think differently and embrace change

- Roadmap for Change: How to put all the pieces together to design and execute successful organizational culture change

This guide is designed primarily for organizations that do not deliver direct services, that are able to continue to work toward their mission relatively effectively through remote work. Some of the considerations and policy options may translate well to direct service organizations, but this guide does not address the unique challenges these organizations face in this environment.

1. Employee Experiences Exclusively Teleworking in Spring/Summer 2020

In mid-March 2020, with little warning, organizations were forced to close their physical offices and immediately create systems to allow staff to work exclusively from home as states and localities issued stay at home orders and shuttered most schools and child care centers in an effort to slow the spread of COVID-19. Organizations that had never embraced routine work-from-home policies or flexible schedules were suddenly given no choice but to adapt in order to continue to advance their mission. And, in the face of a pandemic and a rapidly declining economy, the stakes were higher than ever for organizations with missions related to social justice and those focused on meeting human needs.

Organizations adapted to these conditions in varying ways, but generally had to accept that staff would work from home, work flexible hours, as they juggled new child and dependent care responsibilities, and be granted grace as they grappled with the fear, anxiety, and isolation associated with living during the outbreak of a deadly virus. No one would have been surprised if organizations’ performance suffered.

And yet, many organizations have found that these stressors revealed deep-seated staff commitment to the mission and opportunities to surface new, better ways of doing work. Rather than a dark cloud hanging over the organization’s impact this year, the adaptations have broken the mold on how work can get done. For all the challenges workers face during this time, they have been relatively—or in some cases immensely—pleased with these changes. A survey of more than 800 nonprofit organizations found that nearly 80% of organizations that do not provide direct services are considering maintaining remote work beyond the end of the pandemic.[i]

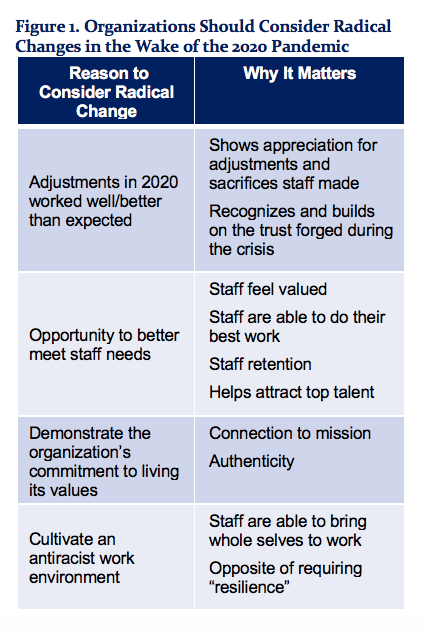

Employee surveys have shown that many employees enjoy the flexibility, increased time for family and personal care, and reduced commuting time and expenses associated with remote work. In one national survey of Americans working remotely during the pandemic, nearly two-thirds said they’d enjoyed working from home, and fully three-quarters are happy with how their companies have handled the transition.[ii] See Figure 2.

Not only is satisfaction up, but most workers report that they are more productive, more collaborative, and face fewer distractions compared to their prior in-person work environment.

Another potential benefit of remote work during this period may be the flexibility it affords staff to respond in authentic ways to the news and protests around police violence and racism. Many nonprofit organizations have an explicit antiracist mission; remote work and work flexibility may be making it easier for organizations and managers to encourage staff to take the time they need to decompress or to participate in protests or other forms of activism. The pandemic has also pushed some organizations to increase their focus on caring for staff mental and emotional wellbeing. This can create new opportunities for internal, on-the-clock listening, reflection, and learning.

Organizations that have not yet surveyed their staff to learn about their experiences during office closures would be well-served to do this before making any decisions about how offices should reopen and what policy changes might be worth pursuing. See the Appendix for a sample survey. As experiences prior to the pandemic suggest, leadership’s best guesses about what’s possible or practical are not always the more accurate predictors of how staff will truly perform—or what they will need—under pressure. It is essential to hear directly from staff and be prepared to consider their input as you move through the pandemic and into the post-pandemic transition.

2. Policy Toolbox

If you have decided—ideally after input and consultation with staff—that you are ready to advance radical change in your organization in the post-pandemic period, the next step is to clarify the specific changes you want to consider making (or institutionalizing, if these adaptations were made during the pandemic). The following toolbox provides a menu of ideas to consider, although it is by no means comprehensive. The ideas here may appear on their face to be about revising the employee manual, but they are not insignificant; they represent the manifestations of culture change. Implementing some of these options is a way to directly reverse some of the most pernicious ways white dominant culture exists and is reinforced in organizations.[iii] They can help organizations push back against using time as the currency by which staff are valued, operating with a continuous sense of urgency, and perfectionism/notions that there is only one right way to do things. The more your plan takes your organization’s norms, culture, and needs into consideration, the greater likelihood the changes will stick.

Download the full article to view the toolbox.

3. Action Planning

The pandemic forced organizations to abruptly shift aspects of their culture on a rolling, and possibly perceived-as-temporary basis. However, enacting lasting changes that propel your organization forward in meaningful ways requires planning. Here are some considerations for leaders charged with executing the change effort. Note that these leaders can—but need not exclusively be—executive and senior-level staff. Valuing voices from across the staff and formally bringing them into the change process is critical.

Risk of Doing Nothing

Fortunately, unlike more conventional change efforts (e.g. those that come about because an organization is underperforming or has a new leader), the choice to institutionalize post-pandemic changes likely already has significant, natural buy-in among staff. That also raises the stakes; staff who have performed well in altered work environments will likely be disappointed if this flexibility is wrenched away from them “when things can go back to normal.” The disruption of the pandemic is challenging the notion that anything can or even should go back to the way it was before March 2020. The dual health and economic crises have laid bare the ways that existing power structures are calibrated to perpetuate racism and inequality. Depending on the positioning and values of your organization, making changes to how you do your work may not be a choice but an absolute imperative, if you are to maintain the trust of your staff, the communities you serve, and even your funders.[vi] Doing nothing in this environment is far riskier than taking bold actions to rebuild stronger, overtly antiracist organizations.

Caregivers and Gender Equity

In this moment, making lasting changes that recognize that high-quality work can be achieved in more flexible environments may be especially important for gender equity. As schools, child care centers, and other caregiving institutions have shut—often for very long stretches of time—the responsibility for caring for children and adults who require care and supervision has fallen largely to women.[iv] Some—disproportionately women of color—have been forced out of the workforce because their jobs can’t be done remotely.[v] Others have chosen to quit their job or work fewer hours to meet caregiving demands.[vi] Still others have cobbled together patchwork systems of care with their partner, family members, or other family “pods” and continued to work full time and care for these family members full time.

Women already earn less on the dollar than men, and although that gap has been slowly narrowing, the pandemic threatens to reverse decades’ worth of progress on wage equality.[vii] The pandemic has wrought such challenging economic circumstances for child care centers that many may be forced to close permanently, altering the landscape for children and those who care for them for years to come.

Addressing the dearth of quality, affordable child care (and after school care[viii]) in this country may be far afield from your organization’s mission. But your policies directly affect whether your organizational culture is one where caregivers—who tend more often to be women—can thrive.

What are you learning about your staff who are caregivers during this time? If they can continue to be productive members of the team, even under this heightened stress, what might be possible when child care centers and schools are able to safely reopen? What difference might it make for this portion of your workforce if they could flex hours in order to pick a child up from school, attend an after-school event, or spend more time with their child(ren) while they are awake? And if they can’t do these things at your organization, how many will seek out other organizations that are embracing more flexible policies?

These are not easy questions with clear answers. But if your organization is committed to advancing equity and inclusion, its policies shouldn’t leave this portion of the workforce behind or with fewer opportunities for advancement because it is resistant to the culture change that would be required to truly treat caregivers equitably.

Fortunately, unlike more conventional change efforts (e.g. those that come about because an organization is underperforming or has a new leader), the choice to institutionalize post-pandemic changes likely already has significant, natural buy-in among staff. That also raises the stakes; staff who have performed well in altered work

Be Bold

An incremental, slow-roll anchored in the old ways of doing things is at best wasting an opportunity, and at worst an affront to the trust that has likely grown during the altered state of work in 2020. Leaders should be willing to question assumptions about how the work gets done, or even what the work should be. That is not to suggest that organizations abandon a healthy fear of “mission creep”; decisions should still be grounded in the mission, vision, and values of the organization. Leaders should reject the impulse (which could be explicit or implicit) to use the climbing unemployment rate as an excuse to underpay, overwork, or micromanage staff. Nor should they use the “passion tax” argument – the notion that offering someone the chance to work in pursuit of a mission they care about justifies unfair pay or substandard working conditions or policies – as a reason to shrug off the opportunity to pursue bold change.[x]

Put People First

The changes organizations should be contemplating now are not technical (e.g. standing up a new process for tracking development leads or revamping an annual conference planning process). These changes are cultural. By definition, that makes the process and approach a more nuanced one that will succeed not through the precision of its Gannt charts, but through the inclusion of staff and the recognition that bold change can—and to stick, ultimately must—be iterative change.

Adaptive Change

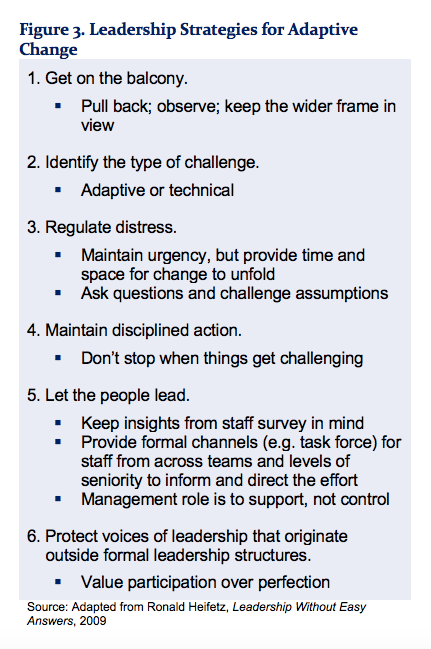

Ronald Heifetz, a leadership scholar and author of multiple books on adaptive change, describes adaptive changes as ones that “require individuals throughout the organization to alter their ways; as the people themselves are the problem, the solution lies with them.”[xi] External factors—a mandate to stay at home and social distance—have forced the initial adaptive changes, but institutionalizing them and introducing bold new ways of doing things is solidly an adaptive challenge. Keep the leadership strategies for adaptive change in mind as you approach and advance your changes. See Figure 3.

Start by making the organization’s implicit assumptions, values, and beliefs explicit. You need to know what your old model for success was and how 2020 has broken this mold in order to reassemble the pieces in a way that reflects the new culture you’re trying to build.[xii]

Choose 3 Levers

Stephen J.J. McGuire contends that organizations are open systems; they naturally work to maintain equilibrium and revert to their prior state when disrupted.[xiii] He argues that sustainable, organization-wide change requires organizations to move at least three of the following levers of change simultaneously in order to sufficiently interrupt the system’s natural tendency to resist change and revert to its former equilibrium: Mission, Policies, Culture, Structure, People, Work, Leadership and Tools.

The three levers that may be most relevant in a post-pandemic transition are:

- Culture – What values emerged or were reinforced in recent months? How do they appear in day-to-day work? How do teams communicate? What informal accountability mechanisms are important?

- Policies – When and where can/must people work? How will performance be evaluated?

- Work – Do people understand their own and their colleagues’ roles and responsibilities? Have staff identified work that is duplicative, inefficient, or ultimately unimportant to the mission that can formally be written out of work plans?

4. Roadmap for Change

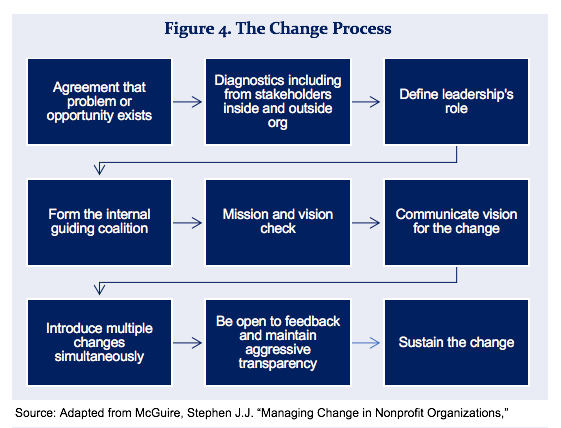

Once you’ve given thought to the considerations in the previous section, you (or the team of individuals leading the change) are ready to follow a sequence of steps to set the strategy into action. See Figure 4 above. The steps recommended here are based on a process outlined by Stephen J.J. McGuire in “Managing Change in Nonprofit Organizations”.

Agreement that the Opportunity Exists

The first three sections of this guide have been dedicated to helping you identify the opportunities and develop the arguments for why they are not only important, but mission-critical. Generating widespread buy-in that change is needed is arguably the most important step of the change process. Is there energy for institutionalizing or changing processes? Given what else the organization is tackling, is change truly important for the organization and for staff?

Diagnostics

Collect information from your staff through a survey, small focus groups, and/or town hall conversations. Collecting information in multiple ways helps ensure all staff are included and have an opportunity to share their experiences. What is working well (or poorly) for your organization right now? Do perceptions vary by role, tenure, or other variables? What are managers learning from performance evaluations conducted since the pandemic began? How are funders reacting to the output/impact of the organization in recent months?

Leadership and A Guiding Coalition

Leaders of strategic change are more effective when they are equipped with vision, commitment to the changes (even when things get hard), emotional intelligence, and strong team-building and conflict management skills. Will a preexisting executive or senior staff team lead the effort, or will a “guiding coalition” or task force be created specifically to lead the effort? Consider how you can build or augment a team to bring all these critical skills to the effort. And if the executive director oversees the group but does not directly participate as a member of it, define a visible, engaged role for that person. Will they update the broader organization on the team’s progress? Attend periodic meetings? Set timelines and milestones? If the executive director does not appear to be bought into the effort, staff will notice – to the detriment of the effort’s success.

Mission and Vision Check

Revisit the organization’s mission and ensure it still rings true. This kind of change effort is not designed to replace a strategic planning process or fundamentally change the purpose of the organization. But if the mission doesn’t accurately describe the organization’s purpose, consider whether a recalibration is needed before you make additional changes. Leadership and staff must be aligned on the “what” and the “why” before you can hope to agree on the “how”.

When you’ve confirmed that the mission is solid[xiv], the guiding coalition should name (or revisit if they have been named previously) the organization’s values and build out the vision for how it will feel to work for, and with the organization, after the changes have been implemented. Jim Collins’ vision framework is a helpful tool for identifying an organization’s values and crafting an “envisioned future.”[xv]

Communicate the Vision

The kinds of changes you intend to make dictate the stakeholders with whom you need to invest time and energy communicating the vision. If the changes are primarily internal, the main audience will be staff (including union leadership if applicable) and the board, but you may also need to communicate the vision to funders if it will affect the ways they interact with the organization. If the changes affect your organization’s public brand, or the ways external partners will interact with it, you should take time to share your vision with them. The most important part of this step is to ensure that those affected by the changes know they are coming and have the opportunity to weigh in and feel heard.

Introduce Changes Simultaneously

Plan, introduce, and begin implementing changes by pulling at least three of the following levers: Mission, Culture, People, Leadership, Policies, Structure, Work, or Tools. See page 11. This can help create the shock to the system needed to help the changes settle and stick.

Incorporate Feedback

Observe and take regular pulse checks on how implementation is going and the effect it may be having on staff, outcomes, and impact. Adjust and iterate as you go. Keeping in mind principles for adaptive change, provide space for those not in leadership roles to speak up, challenge what is not working, and make suggestions for improvement. Aggressive transparency – about what leadership is hearing, who has authority to make changes, how adjustments are being decided upon, and so on –is critical for bringing staff along, nurturing trust, and cultivating a more inclusive and equitable environment.

Sustaining Change

Successful culture change takes time and is never “done”. Create space to celebrate the aspects of the changes that are going well and to honestly invite and listen to feedback and iterate over time. Share your progress and learnings with partners and funders. Be persistent and don’t be thrown off by the inevitable other disruptions that will require new layers of adaptation. And always, always put people first.

[i] Nonprofit HR, “Coronavirus Response Pulse Survey: Results & Insights,” May 29, 2020, https://www.nonprofithr.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/COVID19-II-Pulse-Survey-Infographic-NPHR-for-Publishing-2020.pdf.

[ii] Morning Consult, “How the Pandemic Has Altered Expectations of Remote Work,” July 1, 2020 https://morningconsult.com/form/pandemic-remote-work-preferences/.

[iii] Tema Okun, “White Supremacy Culture,” https://www.dismantlingracism.org/uploads/4/3/5/7/43579015/okun_-_white_sup_culture.pdf.

[iv] Clare Cain Miller, “Nearly Half of Men Say They Do Most of the Home Schooling. 3 Percent of Women Agree.” New York Times, May 6, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/06/upshot/pandemic-chores-homeschooling-gender.html.

[v] Heather Long, “The big factor holding back the U.S. economic recovery: Child care,” Washington Post, July 3, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2020/07/03/big-factor-holding-back-us-economic-recovery-child-care/.

[vi] Caitlyn Collins, Liana Christin Landviar, Leah Rupanner, William J. Scarborough, “COVID-19 and the Gender Gap in Work Hours,” Frontiers, July 2, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12506.

[vii] Danielle Kurtzleben, “How Coronavirus Could Widen the Gender Wage Gap,” NPR News, June 28, 2020, https://www.npr.org/2020/06/28/883458147/how-coronavirus-could-widen-the-gender-wage-gap.

[viii] Afterschool Alliance, “American After 3pm: Afterschool Programs in Demand,” 2014, http://www.afterschoolalliance.org/documents/AA3PM-2014/AA3PM_National_Report.pdf.

[ix] Darren Walker, Are You Willing to Give Up Your Privilege?” New York Times, June 25, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/25/opinion/sunday/black-lives-matter-corporations.html.

[x] Jae Yum Kim, Troy H. Campbell, Steven Shepherd, and Aaron C. Kay, “Understanding contemporary forms of exploitation: Attributions of passion serve to legitimize the poor treatment of workers,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, January 2020; 118(1)121-148, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30998042/.

[xi] Ronald Heifetz and Marty Linksy, “A Survival Guide for Leaders,” Harvard Business Review, June 2002, https://hbr.org/2002/06/a-survival-guide-for-leaders.

[xii] Davia LaPiana, “When Organizational Change Fails,” Stanford Social Innovation Review, August 26, 2016, https://ssir.org/articles/entry/when_organizational_change_fails.

[xiii] Stephen J.J. McGuire, “Managing Change in Nonprofit Organizations,” Ch. 8 in Kathy Kretman, Nonprofit Excellence. Washington, D.C: Georgetown University Press, 2008.

[xiv] If the mission is unclear (with wide variation in interpretations across leadership and staff) or doesn’t accurately reflect the work the organization is engaged in or prioritizing, implementing lasting change will be much harder. Organizations in this situation will likely be better served by resolving their mission misalignment first before wading into culture change.

[xv] Jim Collins, Vision Framework, https://www.jimcollins.com/tools/vision-framework.pdf; Jim Collins and Jerry I. Porras, “Building Your Company’s Vision,” Harvard Business Review, September-October 1996, https://hbr.org/1996/09/building-your-companys-vision.